The Joy of Box

Tuesday, March 27, 2007 → by Robokku

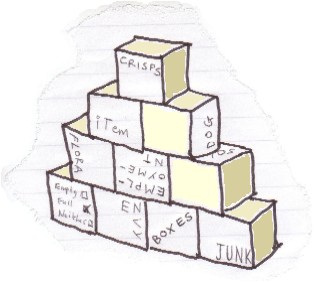

Boxes are plain, powerful things that govern our lives. Once boxed, other, awkwardly various items become movable, stackable, dustable, understandable, loveable and, crucially, ignorable. A boxed item sneaks into invisibility. Clearly labelled, prominently shelved, it is the keen ceremony of storage that talks down the anxious mind and lets the watchful eye drift confidently closed. As we lull in such elaborate certainty of a thing's existence, that thing discreetly lets itself out of our world and silently closes the door. This is how boxes have won the tacit admiration of all humans - and the not-so-tacit admiration of some of them...

My second favourite kind of box is a box-out (see "Boxed Out!")

A box, put simply, is an approximation - a low-resolution representation of its ultimate contents. Knowing this we can see that there are many conceptual boxes in play all around us all the time. Take these many molecules. Some groups of them I call 'nuts', some I call 'bolts'. However, not only are the little molecules thus boxed out of my mind, but even the nuts and bolts are packed away. As a casual, unquestioning cyclist, the nuts and bolts - along with 'spokes', 'gears', 'bearings', 'levers', 'cables' and 'tyres' - are packed clumsily in my head as a 'bicycle'. That concept - that neat entity in which I put my faith as I whirl down the hills - I can know all at once. That's why I trust it. I ignore the contents of that understood box, eliminating what it represents in favour of a sleek, manageable simulacrum.

A box, put simply, is an approximation - a low-resolution representation of its ultimate contents. Knowing this we can see that there are many conceptual boxes in play all around us all the time. Take these many molecules. Some groups of them I call 'nuts', some I call 'bolts'. However, not only are the little molecules thus boxed out of my mind, but even the nuts and bolts are packed away. As a casual, unquestioning cyclist, the nuts and bolts - along with 'spokes', 'gears', 'bearings', 'levers', 'cables' and 'tyres' - are packed clumsily in my head as a 'bicycle'. That concept - that neat entity in which I put my faith as I whirl down the hills - I can know all at once. That's why I trust it. I ignore the contents of that understood box, eliminating what it represents in favour of a sleek, manageable simulacrum.

But there's the danger. When one of those forgotten nuts behind my conceptual cardboard slips off its bolt, my 'bicycle' is unchanged. However, the machine that keeps me off the fast-moving Tarmac might stop doing its job. If only I could face the untidy nuts and bolts of truth I might avoid the danger of a simulacrum strayed from its source - a 'bicycle' which is no longer a good bicycle. But what a beautiful, clean simulacrum it is! So polished and slick, it might just be worth the risk.

And that is the perilous temptation of the box that has forever sated and tormented the mind of man. Now, seal these clutterous thoughts in a four-line package!

"Look! Look at boxes. There is ten. Ten boxes. I count them easy. Neat like I like. Not like mess inside them!"My favourite kind of box is a box file. The name of a box file gives away the function of all boxes, which is to file things. The distasteful mess that lies behind the shelved, alphebetised, face of any office, when tucked into a box, is tucked out of existence. Box upon box upon box. That's just three boxes - again, easily stacked, easily counted. From my desk , I can see approximately one hundred boxes. On reflection, I know that there are many more behind me. But the careful positioning of my chair - which gets the back of my head in between my eyes and some necessary but ugly administrative guts - has created a kind of virtual box, in which many actual boxes are stored away from my consciousness, their untidy contents another layer from my intellect.

Sylvester Stallone

My second favourite kind of box is a box-out (see "Boxed Out!")

A box, put simply, is an approximation - a low-resolution representation of its ultimate contents. Knowing this we can see that there are many conceptual boxes in play all around us all the time. Take these many molecules. Some groups of them I call 'nuts', some I call 'bolts'. However, not only are the little molecules thus boxed out of my mind, but even the nuts and bolts are packed away. As a casual, unquestioning cyclist, the nuts and bolts - along with 'spokes', 'gears', 'bearings', 'levers', 'cables' and 'tyres' - are packed clumsily in my head as a 'bicycle'. That concept - that neat entity in which I put my faith as I whirl down the hills - I can know all at once. That's why I trust it. I ignore the contents of that understood box, eliminating what it represents in favour of a sleek, manageable simulacrum.

A box, put simply, is an approximation - a low-resolution representation of its ultimate contents. Knowing this we can see that there are many conceptual boxes in play all around us all the time. Take these many molecules. Some groups of them I call 'nuts', some I call 'bolts'. However, not only are the little molecules thus boxed out of my mind, but even the nuts and bolts are packed away. As a casual, unquestioning cyclist, the nuts and bolts - along with 'spokes', 'gears', 'bearings', 'levers', 'cables' and 'tyres' - are packed clumsily in my head as a 'bicycle'. That concept - that neat entity in which I put my faith as I whirl down the hills - I can know all at once. That's why I trust it. I ignore the contents of that understood box, eliminating what it represents in favour of a sleek, manageable simulacrum.But there's the danger. When one of those forgotten nuts behind my conceptual cardboard slips off its bolt, my 'bicycle' is unchanged. However, the machine that keeps me off the fast-moving Tarmac might stop doing its job. If only I could face the untidy nuts and bolts of truth I might avoid the danger of a simulacrum strayed from its source - a 'bicycle' which is no longer a good bicycle. But what a beautiful, clean simulacrum it is! So polished and slick, it might just be worth the risk.

And that is the perilous temptation of the box that has forever sated and tormented the mind of man. Now, seal these clutterous thoughts in a four-line package!

Thou blind fool, Box, what dost thou to mine eyes,

That they behold, and see not what they see?

They know what beauty is, see where it lies,

Yet what the best is take the worst to be.

Sonnet 137a, 'Thou blind fool, Box', William Shakespeare

|

|

Links

Links Subscribe via RSS!

Subscribe via RSS!

Via Email

Via Email

Post a Comment